UK offshore wind is at a critical crossroads. While ambitious 2030 targets promise economic growth and a path to net zero, the industry faces mounting challenges in planning, grid infrastructure, supply chains, and financing. What can be done to close these gaps and ensure the UK retains its leadership position?

UK offshore wind is at a critical crossroads. While ambitious 2030 targets promise economic growth and a path to net zero, the industry faces mounting challenges in planning, grid infrastructure, supply chains, and financing. What can be done to close these gaps and ensure the UK retains its leadership position?

By Arindam Das, Partner, Arthur D. Little, Benedikt Unger, Principal, Arthur D. Little

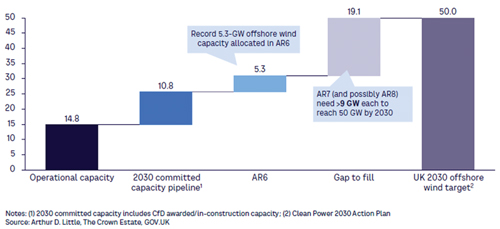

While the UK has made enormous strides in offshore wind, capacity is still behind the government’s target of achieving 43-50 GW by 2030. Allocation Round 6 (AR6), the latest auction to award contracts for difference (CfDs), was a positive step, allocating a total of 5.3 GW of capacity, including resubmissions from earlier rounds. However, this still leaves an estimated 19 GW gap to be filled by 2030, thanks to a combination of challenges. The planning and approval process for offshore wind projects is lengthy and complex, often taking three to five years, while the UK’s transmission infrastructure requires an estimated £70 billion in upgrades to accommodate the rapid expansion of offshore wind to prevent bottlenecks. Additionally, the sector is facing a shortage of manufacturing capacity, skilled labour, and logistical support, alongside financial pressures as rising capital costs challenge project viability.

If these obstacles are not addressed with urgency, the ability to scale offshore wind at the required pace will remain in jeopardy. Going forward, there are multiple areas where both public bodies and the private sector involved in UK offshore wind could look overseas for solutions to key challenges, selectively learning from successes and setbacks in other markets.

In terms of the public sector best practices can be applied around streamlining seabed licensing, more efficient grid connection, and encouraging the creation of a local supply chain. For example, the current UK process for securing seabed leases is fragmented due to the involvement of multiple regulatory bodies. Drawing inspiration from the Danish model, where the Danish Energy Agency provides a one stop shop for approvals would speed up decision making, as would following the Dutch example of offering preapproved zones where environmental assessments have already been carried out.

In terms of grid connection, progress is being made in moving from a queue-based system to a more flexible process but needs to be accelerated. Modular offshore hubs that are already being deployed in Germany and Netherlands, can also be part of the solution. Establishing dedicated offshore wind clusters in regions with strong infrastructure and port facilities, backed by subsidies and tax incentives, as in Denmark, will help develop local supply chains.

The UK private sector can also learn from other countries in order to increase supply chain resilience and coordination and enhance port, transport and installation infrastructure. Investing in domestic production facilities, as in the US, will create more localised supply chains that avoid bottlenecks and create new jobs. Joint procurement platforms could facilitate greater collaboration and coordination between transmission companies, developers, and suppliers while reducing costs for all parties involved. Finally, following the example of Dutch and Belgian ports, such as Rotterdam and Ostend, private sector investment could help upgrade existing UK ports into offshore wind hubs, providing purpose-built infrastructure to support the industry.

Swift action is needed to maintain UK leadership in offshore wind. Leveraging public and private sector initiatives based on best practices from other offshore wind focused countries is therefore essential to better position the country to achieve its net zero ambitions while driving economic growth.