For several years now, I have taught a university course in wind energy. Every year I update the contents of the course to include the progress of technology and the new turbines coming to market. One of the topics is the breakdown of the cost of a wind turbine or a wind farm. One needs to know the percentage cost for different components of a turbine and for various tasks in developing a wind farm. Finding the answer to this question takes a lot of time, without any result. The difficulty stems from the fact that data is not readily available, the numbers are more likely case related, and one can only consider an average even with access to some data. Such information is useful in determining the areas where costs can be reduced by an alternative action or process.

For several years now, I have taught a university course in wind energy. Every year I update the contents of the course to include the progress of technology and the new turbines coming to market. One of the topics is the breakdown of the cost of a wind turbine or a wind farm. One needs to know the percentage cost for different components of a turbine and for various tasks in developing a wind farm. Finding the answer to this question takes a lot of time, without any result. The difficulty stems from the fact that data is not readily available, the numbers are more likely case related, and one can only consider an average even with access to some data. Such information is useful in determining the areas where costs can be reduced by an alternative action or process.By Ahmad Hemami, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

A good study was performed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in 2016 in this regard based on gathering considerable data from the previous years. According to this study, for land-based turbines the major (64.6%) portion of the cost breakdown is as shown in Table 1. This table also shows the same numbers for 2021 for a reference turbine, based on taking into account some indexing for costs and inflation as well as other factors. The cost of a turbine itself, i.e. the rotor, nacelle and tower, constituted 67.3% of the total cost in 2016 and 70.4% in 2021.

|

Turbine |

|||||

| Rotor | Nacelle | Tower | Foundation | Electrical infrastructure | |

| 2015 | 19.1% | 33.1% | 15.1% | 4.1% | 10.3% |

| 2021 | 21.4% | 35.0% | 14.0% | 5.2% | 9.0% |

Table 1. Average data for partial cost breakdown of land-based wind turbines

For an offshore wind farm the costs for foundation and electrical infrastructure are much higher than those for onshore wind farms. Also, the operations (turbine transportation, assembly and erection) are more costly. Some corresponding numbers provided by the same source are shown in Table 2.

| Turbine | Substructure | Electrical infrastructure | Assembly | |

| 2015 | 32.9% | 13.9% | 19.0% | 13.9% |

| 2021 | 33.6% | 12.8% | 17.9% | 10.5% |

Table 2. Partial cost breakdown for an offshore wind turbine

For floating wind farms, the numbers are different than those in Table 2. It is useful to have them here (for 2021 only) for comparison (Table 3).

| Turbine | Substructure | Electrical infrastructure | Assembly | |

| 2021 | 23.3% | 37.5% | 13.4% | 5.7% |

Table 3. Partial cost breakdown for a floating wind turbine

Although the cost of manufacturing turbines is lower for offshore wind farms, it could be lowered further, especially because the turbine size has been continuously growing. Transportation and handling of long blades, now reaching 140 metres (Mingyang MySE 18x-28x) with longer lengths to come, is not an easy task. Also, in many places in the world there is still a lot of opportunity for onshore turbines, and transportation of long one-piece blades can be a real challenge.

Traditionally, the blade manufacturers expanded the same technology to make larger and larger blades. Probably there was no need to think of an alternative way. Just recently I came across a company trying to make modular turbine blades. No blade is yet built.

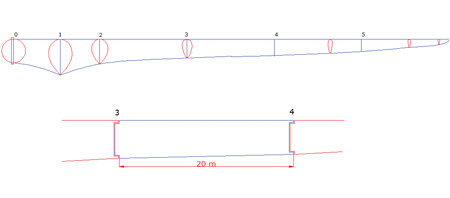

Thinking about modular blades, I believe that there are two different concepts. One is to construct a blade out of short elements that can be fixed together and covered with a proper lining for the required length. In this way a 100-metre blade can be made of say 50 pieces of 2-metre blade segments. Another concept, which places more emphasis on easier and less costly transportation, is to make a blade in a few pieces; for example, a 100-metre blade is broken into five 20-metre segments, as shown in Figure 1. The largest segment in this approach is between points 0 and 2, and the cross-section of the blade is shown in red. At point 1 the blade has the largest chord. The segments can be bolted together and the intersection can be covered with a soft and strong material like Kevlar.

Further Reading

- https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy18osti/70363.pdf

- Hagenbeek, M., van den Boom, S.J., Werter, N.P.M., Talagani, F. et al. 2022. TNO Report: TNO-2021- R12246: The Blade of the Future: Wind Turbine Blades in 2040.

- Mingyang releases 18MW offshore wind turbine. 13 January 2023. https://www.windtech-international.com/product-news/mingyang-releases-18mw-offshore-wind-turbine

- Stehly, T. and Duffy, P. 2022. 2021 Cost of Wind Energy Review. National Renewable Energy Laboratory. https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy23osti/84774.pdf