For the past 150 years oil tankers have been used to transport energy (oil) from the production site to the overseas consumption sites. Unless man wants to destroy the living conditions on Earth, this cannot be continued as in the past decades, even if there still exist reserves of fossil oil and gas. The most abundant sources of renewable energy that so far are economically compatible with fossil fuel are solar energy and wind energy. The best scenario for these renewable energies is that they are captured in not so far distances from their consumption sites. These resources, nonetheless, are not evenly distributed on the earth surface, and like oil we need to transport energy from regions of high renewable energy intensity to regions lean in renewable energy.

By Ahmad Hemami, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

In recent years there have been many studies and research on replacing fossil fuel with green energy, and various techniques have been suggested. The most reasonable practice, from the viewpoint of keeping the process as green as possible, is to use hydrogen. This includes converting green energy into hydrogen, which can be physically moved from one place to another; thus, a way of transporting energy for long distances, where electric power cannot be transmitted, and storing it for long periods. This is applicable to moving energy between continents. It applies also to offshore wind farms as long as energy is brought to shore. But as we move farther into the sea, bringing the captured energy to shore cannot be done in the normal way; that is, transmission through wire.

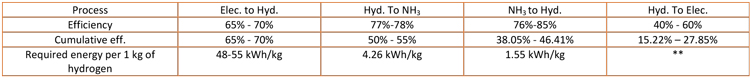

** This process (in a fuel cell) generates heat. In large units this heat can be recovered for useful purposes, but with small applications it might be necessary to remove it.

Table 1. Efficiencies and energy need for the four processes

In general, hydrogen can be burnt as a fuel. However, using hydrogen for generating electricity is more efficient and can be implemented on a small scale as in vehicles or on a large scale as in power plants working based on fuel cell technology. A major technical problem with such a scenario is storage and transportation of hydrogen. From the cost point of view, at almost any distance, the relative energy consumption associated with the delivery of pressurised hydrogen becomes unacceptable [1]. There is a cost of maintaining hydrogen at very low temperature (below -240°C), as well as losing part of the product through leakage and boil-off. And hydrogen is highly inflammable. For these reasons, it has been suggested that storage and transportation be carried out through converting hydrogen into ammonia, and at the consumption site ammonia be converted back to hydrogen. Although this whole may sound technically feasible and can work for many situations, the first question coming to mind is whether it is economically viable for wind energy from floating offshore wind farms.

In the transmission of electricity through cables, after the initial cost for the infrastructure of transformer stations and high voltage transmission lines, the cost of maintenance and energy loss is minimal. On the other hand, for conversion to hydrogen and ammonia and the reverse process, in addition to the infrastructure cost for the required plants, there are continuous cost and efficiency concerns associated with all the following conversion processes: Electricity to hydrogen, Hydrogen to ammonia, Ammonia to hydrogen, and Hydrogen to electricity.

The efficiency of each process depends on a few parameters such as the temperature and pressure conditions, as well as the process itself (for instance, the type of catalyst employed). For example, with 100%F efficiency, to produce 1 kg of hydrogen, 32.935 kWh of energy is required. For the electrolysis of water, the process efficiency is about 70% and up to 50 kWh of energy is needed for 1 kg of hydrogen. Also, a process may be very energy intensive and require elevated temperature and pressure. The process of making ammonia from hydrogen, for instance, is by the catalytic reaction of nitrogen and hydrogen. This process requires high temperature and pressure (400 - 600°C and 200 - 400 bars). Moreover, process efficiency and financial viability can depend on the size of a plant, meaning that for small plants the cost can be very high and the operation not profitable.

Putting aside the cost of plants for each of the four processes (which, indeed, can be the major expenditure) and focusing on efficiencies alone, it can be seen from Table 1 that the total efficiency can be as low as 15%. This means that the cost of electricity output after conversions compared to electricity from nearby wind farms is going to be between 3.6 to 6.6 higher. This excludes the infrastructure and transportation costs.

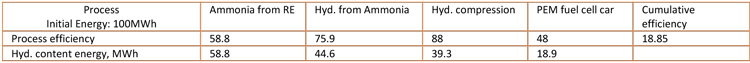

Table 2. Roundtrip efficiencies and balance of energy for renewable energy conversion

A similar table [2] (see Table 2) shows the efficiency and energy in hydrogen content after each of the above processes, starting from 100 MWh energy. Although the end result is meant for use in a fuel cell for vehicles, the numbers clearly show the decline of the amount of hydrogen content after a roundtrip through the four processes. In this work the required energy for each process is subtracted from the initial value. But the transportation cost is not included (In 1 kg of ammonia, the net hydrogen energy content is equivalent to 5.2 kWh).

Also, considering that normally the process plants are not automated and need operators, putting all the facts together one can conclude that the scenario of converting energy into hydrogen is not applicable to floating wind farms very far from the shore.

Further reading

[1] Ulf Bossel and Baldur Eliasson: Energy and the Hydrogen Economy, https://afdc.energy.gov/files/pdfs/hyd_economy_bossel_eliasson.pdf

[2] S. Giddey et al: Ammonia as a Renewable Energy Transportation Media, ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2017 5 (11), 10231-10239