After continuous growth to 12MW (Haliade 12), now the wind turbine manufacturers are targeting 14 to 15MW, and 20MW turbines are expected to be available within a few years. But how far can this continue, thinking about the large mass of the nacelle, the yaw system and all the other components? Will there be any new design entering the race or will the three-bladed horizontal axis wind turbine (HAWT) in its almost standard form continue to be the norm for wind turbines? It can be envisaged that for some time this will remain the norm until a breakthrough happens.

After continuous growth to 12MW (Haliade 12), now the wind turbine manufacturers are targeting 14 to 15MW, and 20MW turbines are expected to be available within a few years. But how far can this continue, thinking about the large mass of the nacelle, the yaw system and all the other components? Will there be any new design entering the race or will the three-bladed horizontal axis wind turbine (HAWT) in its almost standard form continue to be the norm for wind turbines? It can be envisaged that for some time this will remain the norm until a breakthrough happens.By Ahmad Hemami, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

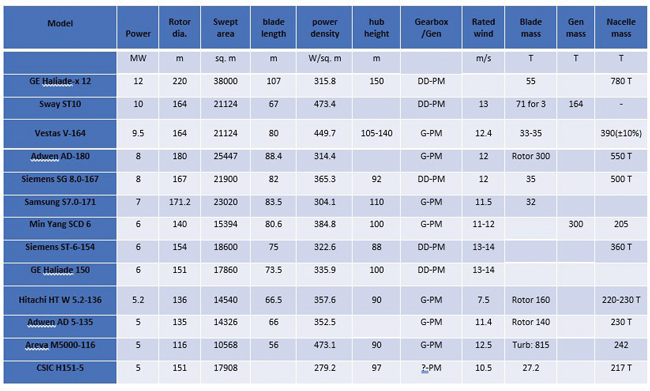

The trend so far has been to replace the doubly-fed induction generator (DFIG) with a permanent magnet generator to reduce the cost of maintenance – although this is yet to be proven with sufficient data – and to reduce the tower top weight by eliminating part of or the whole gearbox.

I have collected data to compare the generator weights for geared or direct-drive wind turbines with those with a DFIG. A few of these with their component weights, as far as available, are shown in Table 1. Based on the weights of the major components (blade, nacelle, generator) one model stands out, and a further search (Figure 1) illustrates a significant difference in design between this turbine and the common three-bladed HAWTs. The corresponding website shows more interesting features, like 20% less cost for generator.

If this structure for the generator and its integration with the rotor is promising, then this is the way to go for the newer and larger wind turbines. Continuing to dig deeper into the matter while feeling this was a breakthrough for the weight reduction of the growing giants, I was surprised to find out that this turbine does not exist. In fact, it has never been built and the 10MW turbine, with all the claimed advantages is only on paper.

A recent publication, written by Eize de Vries for Windpower Monthly, introducing some 40 turbines failing to survive in operation indicates the challenge for success when it comes to wind industry. These failed products, even some of them from famous and successful manufacturers, could not perform satisfactorily in the environment run by a challenging nature and the competitive market.

In the list, I have seen the turbines manufactured by Clipper, an American manufacturer. I visited the manufacturing plant several years ago when it was still making a few models of around 2MW turbines. The Clipper turbine was different than the more common design. The gearbox and connection of the main shaft to the hub allowed access to the inside of the blades without the need to climb the nacelle. This was a (minor) advantage for those frightened of height. Apart from the heavier weight of the nacelle assembly (requiring a larger and heavier tower), I believe the main problem was with the four parallel generators that were powered by four output shafts from the gearbox. Apparently, in a battle with rival companies, this design could not last long.

In the list, I have seen the turbines manufactured by Clipper, an American manufacturer. I visited the manufacturing plant several years ago when it was still making a few models of around 2MW turbines. The Clipper turbine was different than the more common design. The gearbox and connection of the main shaft to the hub allowed access to the inside of the blades without the need to climb the nacelle. This was a (minor) advantage for those frightened of height. Apart from the heavier weight of the nacelle assembly (requiring a larger and heavier tower), I believe the main problem was with the four parallel generators that were powered by four output shafts from the gearbox. Apparently, in a battle with rival companies, this design could not last long.The evident reality is that unless a turbine has proven its performance, the users are less likely to take a risk on new or unknown performance, particularly when the cost is higher, which includes larger turbines. This is a trend that can be seen with all the major successful players, where they started from turbines with a fraction of a megawatt power and are now aiming for 15 and towards 20MW. This can make it difficult for newcomers to the industry, even with a brilliant idea or design. But that is the way it is. Undoubtedly, the industry needs to prove functionality.

Although every aspect of the operation of a complex system like a wind turbine must start from scientific work on paper, that is not sufficient to prove the functionality and performance of a product such as a 10MW turbine. There is a huge difference between the paperwork and the physical device based on that paperwork. A more logical way is probably to start with a 1MW turbine, even if it may be difficult to sell because of the small size. Or, even a smaller size like 100kW can serve to pave the way for a larger product to be manufactured. Starting with a 10MW turbine looks like bypassing the lower steps on a ladder and aiming for the upper part.

On the 40 list, one can see a few examples of turbines with an uncommon design that could not hit the market, as well as a few more without a prototype. I wonder whether there has been any wind turbine with the opposite scenario, that is, whether a successful product has been sold before it was made (unless the manufacturer could provide a warrantee of absorbing any losses). It is likely that the long-term future of wind turbines will involve a vertical axis design, but any new idea/design must definitely overcome the odds.