I intended to perform an analysis and comparison of wind turbines with doubly fed induction generator (DFIG) and those with permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG) in terms of reliability and weight issues. The reason behind this comparison is the fact that these two issues are the most important matters pertinent to how profitable a wind turbine is in its life cycle. Reliability determines the possible downtime and loss of revenue through the entire life of a turbine, while the weight (of what goes on top of a tower - the nacelle and rotor) affects the initial cost of the tower and its foundation as well as transportation and installation, particularly for offshore turbines, for which the cost of any operation is much higher than for onshore machines.

By Ahmad Hemami, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

The question is whether, in the same way that today video-cassette-recorders are replaced by newer technologies, or like film cameras that probably are entirely out of production, doubly fed induction generators have served the wind industry for some time, paving the way to its advancement.

Conducting the initial survey to gather the necessary information, I found this task to be very hard, mainly due to lack of sources that provide such information, even the turbine manufacturers. A second reason is that many turbines that once were probably a candidate for becoming a star, are already gone. I found more obsolete models than working models. This survey focused on turbines with about 5 MW capacity and up; so, the ones that are already outdated were not even considered. It is not unreasonable to assume that for future onshore turbines the power range that can become standard is 5 to 7 MW, and for offshore anything over 8 MW, at least for the present time. We hear about work in progress for development of a 22 MW turbine [1].

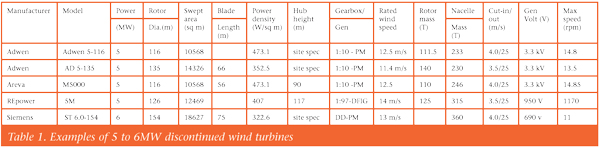

For some time, a DFIG has been the intelligent choice for almost all wind turbines. The power rating of electronic converters was about one third of the total turbine output power, and it could work in sub-synchronous mode as well, for low-speed winds. On the other hand, a DFIG has brushes that must be serviced and replaced. In conjunction with an attempt to find a solution to gearbox problems together with improvements to the electronics, leading to more reliable power converters, synchronous generators became preferable. This is particularly indorsed using permanent magnets instead of electromagnet in the rotor. Even with 5MW turbines, DFIGs gave way to permanent magnet synchronous generators, as can be observed from the data in Table 1.

Until a few years ago, all turbines shown in Table 1 were available and operating. Now all are considered discontinued. More likely they paved the way for larger and more powerful turbines. The chain of actions and logic in this process can be seen. As previously pointed out [2], using two sets of converters in a back-to-back configuration (as is customary in DFIG) is probably not very economical. A synchronous generator for wind turbines, on the other hand, MUST operate at different speeds and it NEEDS to work through power converters. The required converters, then, MUST be full-size. Finally, if full-size power converters are inevitable, then, as introduced by Siemens in 2011, why use a gearbox? Hence, the introduction of the direct-drive approach.

We see that despite some drawbacks of PMSG the newer (and larger) turbines use the technology with or without a gearbox. The trade-off between involving a gearbox or using direct-drive technology appears in weight and price. The magnets are based on rare earth materials and are very expensive. A PMSG, thus, is heavier than a DFIG, due to a larger number of poles for direct drive. However, if a PMSG uses a single-stage gearbox, as far as a PMSG and an electrically excited synchronous generator (EESG) are concerned, there might be a weight decrease in favour of using a PMSG rather than a wound rotor generator (EESG), depending on the number of poles. Nonetheless, eliminating the gearbox does not imply a reduction in either cost or weight, because for lower speed (gearless) operation the number of poles must be increased. The increase in the number of poles is necessary from both electrical (for frequency) and mechanical (for providing the required torque on the shaft) points of view. This implies a larger diameter and a greater number of magnets, which translates into larger bearings, a larger and heavier machine, harder transportation, and consequently a higher price tag.

There are two other differences between PMSGs and EESGs worth mentioning. In an EESG, the current in the rotor winding can be varied. In conventional power plants this allows correction of the power factor. On the other hand, there is a copper loss in an EESG due to the rotor current. Neither of these issues arises with a permanent magnet machine. Nonetheless, there exists a potential enigma - magnets can demagnetise. If this happens to those in a generator, the power level declines. And this is similar to what has been experienced in the past with gearbox failure.

It took a long time (with the older machines) to notice the vulnerability of the gearbox and to realise/analyse the cause. Probably, with the speed of growth and obsolescence of wind turbines, we do not yet have sufficient data and a prediction about what can happen to the magnets and what the outcome will be.

Further Reading

- 'Mingyang introduces two new wind turbine models'. 23 October 2023. https://www.windtech-international.com/product-news/mingyang-introduces-two-new-wind-turbine-models

- Hemami, A. 2021. Two Modes of Operation in Back-to-Back Converters for DFIGs, Is It Worthwhile?' Windtech International November/December, page 10.